Rethinking a Building’s Potential

“By expanding traditional ideas about rehabilitating and retrofitting commercial properties to include building use, it is possible to create value where previously there wasn’t any,” asserted Richard Brennan, an architect and Partner at the multidisciplinary design practice, HLW International. “Would you go to a doctor for a facelift when what you really needed was major surgery?” The more effective question to ask then becomes what will it take to align the building with a target tenant base?

Brennan cautions that changing real estate markets and economic factors over the last decade have dictated that older buildings accommodate uses disparate from their original design intents. Location is often the consistent determinant, regardless of where on the spectrum of renovations and upgrades a repositioned property might fall. This is because structural modifications can expand a building’s market to attract a more diverse range of tenants—enabling an aging building to be more competitive in an established business district or marketing an awkward floor plate as compatible with an alternate tenant type.

Whether upgrading to Class A office space or radically rethinking the program uses, a number of variables can come into play in the repositioning decision making process. These can include program demand, technical feasibility, and the return on investment for leasing versus owning. Significantly, though, a deliberate, strategic change in the tenant profile can be a positive financial alternative.

Pat Hauserman, First Vice President at Tishman Construction, an AECOM company, recommends assessing a property from an investor or owner’s perspective. “We ask questions, such as whether the asset is performing at market rate, what is its potential, and how can it be improved to increase financial performance. Similarly, is the asset a ‘hold’ or ‘invest for resale’ type asset? Has the rental income been maximized? How little can be invested to get the best return?” The answers to these questions inform decisions about which design and construction approach will realize the best potential value of the asset.

According to Newmark Grubb Knight Frank (NGKF), a leading commercial real estate advisory firm, the average age of buildings in New York City is approximately 82 years. “It varies, of course, from [New York City] neighborhood to neighborhood, but with repositioning investments of $100 – $250 per square foot, annual rental increases of $10 – $20 per square foot are common,” said Dennis M. Karr, Managing Director in NGKF’s New York office. “These numbers are even greater for emerging neighborhoods and for what we call the ‘wow factor buildings’.” Similar statistics can be identified for central business districts and newly recycled neighborhoods across the country.

But where and how to invest?

Successful development projects are focused on designing and building to meet the targeted needs of specific tenants. Jennifer Brayer, HLW’s Partner-in-Charge of the design, renovation, and upgrade of several million square feet of space for JPMorgan Chase in Manhattan, offers the following advice. “For example, HLW knows Class A office space inside and out, from the amenities and high-end finishes to the floor plans appropriate for financial and corporate tenants with sophisticated space and technology requirements. However, it is just as important to understand how the key business drivers for a proposed user of a space can line-up with design objectives. In fact, it is critical to understand this prior to investing in the retrofitting of an existing property.”

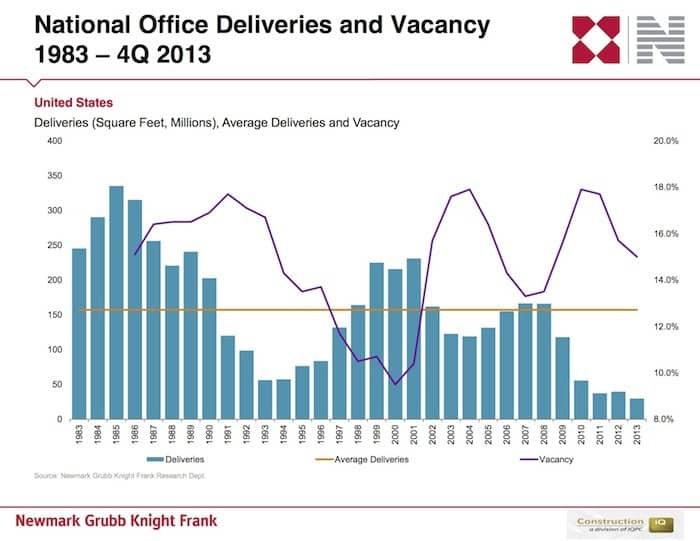

Commercial Office Construction, 1983 to present, at an all-time low

Having a committed owner, an integrated design team, and an experienced contractor working in harmony is key to the development of a comprehensive approach to a project’s scope. Under these conditions, complex construction challenges can be resolved consistent with business drivers—for example, current work strategy trends, including increased density and floor plan efficiencies, aligning with a design and construction approach. It is also possible to create a uniform solution responsive to specific floor conditions and, when applicable, to preserve a building’s innate beauty.

The specific statistics can vary so much from building to building that it is not possible to determine an average return on investment for repositioning older, underperforming assets. The target ROI is ultimately determined by the investment strategy. However, there are key themes and indicators that can provide context. For example, for many buildings, a repositioning strategy focused on increasing building performance ultimately creates cost savings (often more than 15% over baseline energy efficiency), which is typically annualized for the life of the building. In some cases, this essentially pays for the capital investment in a matter of years. 1095 Avenue of the Americas in New York City is a Tishman managed repositioning project, completed in 2009, involving energy efficient recladding and MEP infrastructure upgrades. These investments reduced operation expenses and led to increased rental rates.

Much of the curtain wall installed between 1950 and 1980 has a life expectancy of 20 years. As a result, many buildings in the marketplace have failing wall systems and building infrastructure. Upgrading these essential building components greatly increases a building’s life cycle. 330 Madison Avenue and 100 Park Avenue are successful examples of Midtown Manhattan towers where the installation of a new curtain wall over the existing facade (versus re-cladding) proved the best solution for maintaining tenant comfort, while also transforming the property.

“We evaluated many options for a new façade at 100 Park Avenue with tenant operations, long-term performance, and economics in mind,” said Edward Piccinich, Executive Vice President of SL Green Realty Corp. The fully integrated real estate investment trust (REIT) is focused on acquiring, managing, and maximizing the value of Manhattan commercial properties, as per the company’s website. “Our final selection of an over clad curtain wall system was the right choice. It was flawlessly executed and was a major factor in the success of the building redevelopment and it being awarded BOMA’s International Renovated Building of the Year.”

“You have to think bigger than the building; you want to invest in the fabric and long livelihood of a neighborhood.”

Tishman managed the construction for both 330 Madison Avenue and 100 Park Avenue. The buildings were occupied during construction, but subsequently attracted premium tenants and achieved full occupancy upon the projects’ completion. The owners have benefited from additional savings on taxes through ICAP (Industrial & Commercial Abatement Program) filings and through ongoing operating expense efficiencies. The availability of property tax incentives, such as ICAP, provides a financial vehicle to offset the capital investment required to reposition a property. In addition, there are national tax programs, such as EPAct 2005, which provide up to $1.80 per square foot in one-time write downs for capital expenditures associated with energy improvement upgrades.

You have more options than you think…

Structural modifications to buildings can be costly but are justified by providing owners with a wider array of program options, yielding new and more profitable uses. Significantly, though, substantial modifications to a building, such as full recladding or the removal of the roof, columns, or walls, should be tactical and precise in the execution.

The Reserve, Los Angeles, CA, former post office, now commercial development

“Building owners and their tenants have more options than they realize when it comes to an acceptable use for a building,” said Brennan. “Not all that long ago, urban manufacturing loft buildings were considered unfit as homes. Society has changed. Now, from SoHo to Seattle, loft spaces are not only in demand as places to live, they command premium prices and influence the design of new residential construction. Our approach to commercial buildings has been subject to a similar transformation. Real estate and economic conditions have enabled brokers, owners, facility managers, and tenants to consider unusual options for buildings.”

HLW has designed a number of building repositioning projects across the country involving radical transformations. The Reserve in Los Angeles, CA, is a 380,000-square-foot, former post office distribution building now converted into a commercial complex that caters to creative office and entertainment-related tenants. As a result of Hofstra University partnering with North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System (the third largest health system program in the nation), the former New York Jets’ training facility is now a state-of-the-art medical college.

Red Bull Headquarters, Santa Monica, CA, former warehouse

Light industrial building stock in Santa Monica, CA, is particularly well suited to the needs of a creative clientele. For IMAX Corporation, HLW transformed a warehouse into a film production studio and offices. The roof was raised to accommodate a 25’ high IMAX screening room. Satisfied with the results, IMAX renewed their lease last year, for ten years, at a rate of $46 per foot. The new Red Bull Headquarters met similar expectations and more; sometimes a building’s image is as viable of a selling point as function. HLW’s extensive renovation of an existing 100,000-square-foot industrial building included the insertion of a major sculptural element. The Wave is a continuous form, 40’ wide by 420’ long, which emerges at the entry courtyard and terminates at the other end of the building. In addition to serving as an organizational element for the various public/private zones, it is an embodiment of a corporate identity centered in Southern California surf and skate culture.

Location, Location, Rehabilitation

A project’s location can be a primary building repositioning driver because of visibility, history, or access. Conversely, reuse of a building in a less desirable area can reduce real estate costs to the point where major modifications become cost effective. Sometimes, location is so critical and a program so important, that actual constructability becomes more critical than cost. For example, if you are a nationally known, major broadcast network and you want to have a significant studio presence in New York City’s Time Square, your options are limited. You could purchase a parcel of some of the most expensive real estate in the world and construct a new building, or you could enter into a long-term lease with a landlord amenable to making the changes such a project requires. This was exactly the situation when HLW was enlisted by a confidential media client to help transform an occupied, high-rise office building, dating from the 1970s, into a multi-level TV studio.

Whether it’s the pressure of location or programming that drives somewhat radical building repositioning solutions, timing can also be a critical factor. In the depths of the recession, during the summer of 2009, the for-profit education company Met Schools negotiated a 20-year lease for 203,000 square feet in the landmarked 1921 Cunard Building in Lower Manhattan. This was a leap of faith for the landlord during a down market but one that solved a problem for a historic structure with peculiar shaped floor plates. Although less than ideal for most commercial office tenants, the space was perfect for the school. HLW’s design capitalized on the building’s inherent potential for daylighting and small classroom configurations. In addition, eleven columns were removed from the second floor and the entire area reframed to allow for the insertion of a gym and a four-lane, 25-meter pool.

Location can be a secondary concern for some tenants. In this type of situation, timing combined with real estate costs are most likely the driving factors behind repositioning a property. A joint venture between Disney-ABC Television Group and Univision Communications Inc., to create the new network Fusion, necessitated a large quantity of studio, production and office space in the Miami area. The resulting project is an exceptional example of how properties outside central business districts become excellent performers through radical transformation. The 100,000-square-foot, high bay, tilt-up concrete warehouse was a good deal at less than $10 per square foot in annual rent, even considering that it is located on the take-off flight path from Miami International Airport. In response, HLW’s design solution created a concrete bunker of a building inside the existing building. To achieve the necessary heights for ideal broadcasting conditions, the project raised the existing roof and placed above it an 8” slab. The coordinated efforts of the design and construction teams ensured that the project’s completion was in time to meet a very aggressive on air date.

A closing thought…

“There are many ways to be strategic and proactive about intelligently navigating those transitional periods during the repositioning process. The objective is to mitigate any costs resulting from working around existing tenants, when possible, while still benefiting from maintaining an existing cash flow,” cautioned Brayer. A smooth transition from one population of tenants to another—for example, from lower to higher rents or from one industry to another—is the surest way to build something truly viable and substantial. Brayer continued, “You have to think bigger than the building; you want to invest in the fabric and long-term livelihood of a neighborhood.”

Have you asked the right questions?

Is it necessary to replace the façade to improve the appearance and operational/energy performance of the property? If so, should it be an over-clad, re-clad, or just a glazing replacement? Will the energy code impact this decision? If so, what are the implications for perimeter MEP system upgrades? What is the best approach to minimizing disruption to existing tenant operations, and what is the most flexible approach? Is the lobby being used efficiently? Is its aesthetic in line with others in premium market position? Could it be re-designed to incorporate more retail? Are the elevators performing efficiently to maximize vertical transportation through the building? How can the overall approach to logistics be implemented to avoid tenant demands for rent abatement or concessions due to construction operations?

– Provided by Tishman Construction, an AECOM Company.