Ever since the May 2010 ‘flash crash’, regulators on both sides of the Atlantic have adopted U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s ‘I know it when I see it’ mindset towards high-frequency trading, rather than formally defining the practice themselves. However, the EU and European Securities and Markets Authority have painted themselves in to a corner with MiFID 2 and MiFIR.

Under MiFID 2, trading firms will need to synchronize their server clocks to coordinated universal time (UTC) so regulators can precisely reconstruct market activity from time stamps.

If a firm trades via voice or uses a request-for-quote (RFQ) system where human involvement is necessary, those trades need to be time-stamped in one-second intervals that can have no more than a one-second divergence from UTC time. High-frequency, algorithmic trades need to be time-stamped in a microsecond interval that cannot have more than a 100-microsecond divergence from UTC. Finally, any trades do not fall into the previous two buckets must be time-stamped with a one-millisecond increment and cannot diverge from UTC time by more than a millisecond.

Determining whether a trader used a voice system is simple. But determining which of the two electronically executed buckets a trade falls into, not so much.

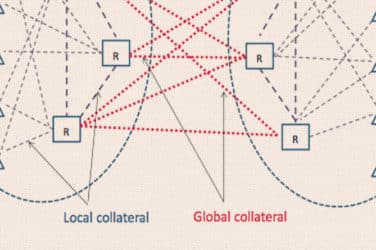

European regulators have two approaches that they might use to define high-frequency automated trading.

The first, which is used by German regulators, would be to define a specific threshold of message rates. Its simplicity makes it attractive. But as soon as the regulators draw an arbitrary line in the sand and say “no faster message rate than that,” the limit would quickly wind up out of date as network message rates continue to increase as the technology evolves.

The second approach would involve trading venues identifying firms that have a median order lifetimes lower than the median order lifetime of all of the other orders on the trading venue. Once a venue identifies a firm using such a technique, that venue member would be treated as using the same technique on all other EU trading venues, according to regulators.

Again, the regulators do not get down into the weeds and say how much lower a firm’s median order lifetime must be compared to the rest of the orders trading on the the same venue.

Yet, if the regulators expect firms to meet the January 2017 deadline for MiFID 2 compliance, someone will need to bit the bullet and actually write down a number. If not, the EU is going to need to grant the implementation delay the industry has requested since no one will know the messaging limit and how granularly they will need to synchronize their server clocks.