With cyclical and secular trends driving the recent decline in block trading volumes, the buy side has to find smarter ways of interacting with fragmented liquidity to execute large size orders.

The macro trend: a lack of conviction

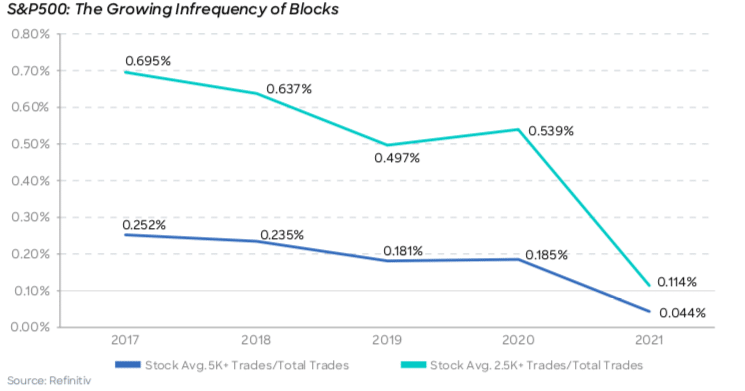

According to Liquidnet data, block trades of greater than 10,000 shares accounted for an average of just 0.026% of each S&P 500 stock in 2022, compared with 0.114% in 2017. This equates to a 77% decline in the frequency of block trading as a percentage of overall trading.

Jeff O’Connor, Head of Americas Equity Market Structure at Liquidnet said the current macroeconomic conditions and volatility are making buy-side traders wary of trading large blocks due to the fear of adverse selection.

O’Connor added: “By the end of 2022, fund manager surveys alluded to the extreme levels of de-risk behavior, and money manager levels of cash at magnitudes not seen since the early 2000’s. There is uncertainty, apprehension and trepidation towards the market, and in particular the large print at a single price in time.”

There was a high level of real price volatility in 2022 with major indices often moving more than 1% in either direction in a single day. These moves are happening with a consistency and frequency not seen since the Great Financial Crises. Investors are also becoming very underweight in US equities, as they look to other regions for more attractive opportunities, and historically high U.S. correlations are making it a difficult time to make fundamental decisions.

The secular trend: redefining the value of the block

Seven to eight years ago, average daily volume in the US marketplace was 6.5 billion shares. Yet, although ADV has doubled since then, the depth and quality of liquidity has diminished according to O’Connor, along with a major shift in the source of market volumes.

From a secular perspective, the longer term reduction in stock split behavior has contributed mightily to the decrease in block trading. The S&P 500 index has appreciated more than 300% since 2011, driving the price of individual stocks to many multiples of where they were a decade ago. Therefore, a $1m trade now involves a far smaller number of shares and O’Connor suggests that block sizes should be redefined.

“Largely, the definition of a block at 5,000 or 10,000 shares has not changed since 2005,” O’Connor added. “That’s why we created a dynamic model that shows the relevant block size for an individual stock and the percentage of fills in the marketplace.”

This model optimizes the minimum fill size to ensure appropriate levels of block-seeking per symbol, while preserving the exclusivity of trading with a select few large orders in a particular stock.

O’Connor advised that investors should be willing to trade blocks algorithmically by using a liquidity-seeking algo, and traders can use minimum-fill quantities more appropriately to reduce information leakage. Venue selection is also very important and O’Connor argued that an unconflicted model is probably the right place to start.

He said: “Ultimately, the appetite for blocks will return with a healthier marketplace. The need for institutions to trade blocks will always exist and long term success in block trading will remain tied to innovation — bringing electronic solutions to what is currently done manually and high touch. And that’s what Liquidnet has been doing for the past 20 years.”