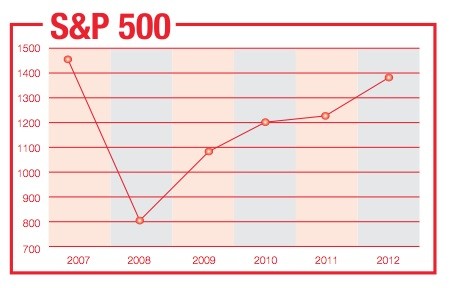

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index stood at 1,380 in mid-November, down about 5% from 1,450 five years earlier. To a visitor from Mars, the similarity of the numbers could suggest that it was a quiet period for financial-market participants.

But in reality, it has been the opposite, as the past five years has been perhaps the most tumultuous half-decade period in the history of global markets.

The fragile, end-of-rally market of late 2007 gave way to a full-blown financial crisis by September 2008, the nadir of which which lasted into 2009. Massive interventions on the part of governments worldwide staved off a doomsday scenario, setting the stage for some stabilization and a market rebound in 2009-2010. But the recovery has yet to sustain itself, and 2011 and 2012 have proved largely disappointing.

“The past five years will likely be viewed as a landmark period of timeless case studies within the history of financial markets,” said Karim Taleb, principal of investment manager Robust Methods.

Karim Taleb, principal of investment manager Robust Methods

And that’s just the broad recap. Each sector of the market ecosystem has had its own travails, ranging from aborted exchange mergers, to hedge funds failing to deliver alpha, to market-structure glitches that have roiled trading desks. But there have also been highlights, including advances in technology and connectivity, improved institutional risk management, and possibly, the groundwork for a more effective regulatory system.

Aside from parsing the five years that have passed, it’s also worth looking ahead to the next five years. On balance, the expectation is for a pick-up in trading volumes and an increase in market valuations, though opinions vary widely as to when that will occur, and to what degree. There are sure to be disruptions, but likely not of the magnitude of what was experienced four years ago. And the regulatory smoke will clear at some point, leaving not necessarily the rules that market participants want, but at least certainty regarding what the rules are.

If there is one sure thing about the next five years, it’s that the time period won’t play out exactly as anyone expects it to.

What follows is a five-year retrospective, and look-ahead, by sector:

INSTITUTIONS

The financial crisis of 2008-2009, plus its lead-in and aftermath, provided a rude awakening for institutional market participants.

“For institutional trading this was one of the most challenging market environments that I have witnessed in my career,” said Steve Hedger, head of equity trading at Fifth Third Asset Management. “Lack of liquidity, extreme volatility, and a disappearance of several venerable brokerage firms made seasoned traders earn their keep.”

The challenges for institutional traders such as Hedger revolve around liquidity sourcing-that is, finding sellers for buy orders and buyers for sell orders. Aside from the demise of Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, other liquidity sappers include tightening regulation of Wall Street, which has prompted surviving big banks such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley to pull in their trading horns, and a more general malaise and mistrust among buy-side investors, both retail and institutional.

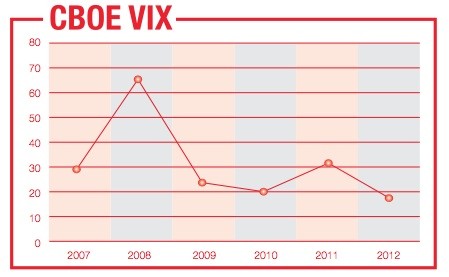

The extreme volatility that Hedger referenced included periods such as August 2011, when macro concerns regarding the U.S. budgetary impasse and the European debt crisis boiled over, sinking stocks and driving the widely tracked CBOE Volatility Index to multi-year highs. There also have been episodes of intra-day volatility caused by market-structure glitches, most notably the so-called flash crash of May 2010.

“The past five years has taught traders to expect the unexpected,” continued Hedger, a market veteran of more than 20 years.

Handled volume of stocks listed on the New York Stock Exchange averaged about 40 billion shares per month from 2005 to 2007 inclusive, according to NYSE Euronext data. That figure spiked to as high as 77 billion in October 2008, but has settled to around 26 billion shares per month in 2012, or about 35% less than pre-crisis levels.

Fundamentals continue to bedevil institutional investors, as sluggish global growth has dimmed the appeal of stocks and compressed bond yields to near historical lows. Also, the economic tumult from a few years ago put government action front and center, and the often-unpredictable decisions of politicians in Europe and the U.S. remain a key focus.

Roger Aliaga-Diaz,senior economist with the investment Strategy Group at Vanguard

“The Great Recession made institutional investors focus much more than before on macro trends and economic policies as key risk factors,” said Roger Aliaga-Diaz, Ph.D., senior economist with the investment strategy group at Vanguard. “Many investors struggle to see the ability for equities to pay a reasonable risk premium, given the prospects of slow growth for earnings and for the broad economy. Others are reasonably disappointed with fixed-income assets.”

“Fears of high inflation due to the Fed’s massive interventions are also pervasive,” Aliaga-Diaz continued. “Some even may think that the traditional investment paradigm has been permanently affected; they argue that a new normal for the economy must lead to a new world for investments and this would need new investment strategies or new asset classes.”

Fixed-income investors had a bumpy ride over the past five years, especially given that bonds are generally more stable investments. Valuations fluctuated, and liquidity waned as regulatory developments including the so-called Volcker Rule in the U.S. prompted some big banks to pull back.

High yield bonds offered more than 2,000 basis points more than U.S. Treasuries at one point in 2008, implying investors would break even if fully 90% of high yield issuers defaulted within five years. “To put that in perspective, the implied default rate in the depths of the crisis was over double the actual default rate of the Great Depression,” said Jesse Fogarty, portfolio manager at Cutwater Asset Management.

“The last market cycle gave witness to both historic high and low valuations, where skilled asset managers could have provided significant alpha to their portfolios by navigating market extremes,” Fogarty said. “While bells don’t ring at market tops and bottoms, the manic lows and highs reached over the last five years are probably the closest thing to definitive signals that investors can ever hope to receive.”

One institutional-investment strategy that was discredited over the past five years was the notion that as long as a portfolio was sufficiently diversified, big losses could be avoided, even in bear markets.

But the global crisis that was marked by tail-risk events such as the collapse of banking stalwart Lehman brother also was accompanied by a dramatic and unprecedented increase in correlation across asset classes. So whereas declines in some securities typically had been offset by gains in others, screens went red across the board in 2008 and early 2009.

“Prior to the global financial crisis a portfolio invested in low or non-correlated assets served investors well,” said John Brown, global head of client development at Intech Investment Management, a Janus subsidiary which manages $39 billion. “Then came 2008, and the investing world was turned on its head. Assets that typically had low correlation to one another suddenly became perfectly correlated.”

“As a result of this new paradigm, risk management is now and should continue to be perhaps more important than ever,” Brown said. “We anticipate that over the next five years risk management will continue to stay top-of-mind for investors as well as for the firms that are entrusted to manage their assets.”

The diversification dislocation resulted in pension plans-considered among the most conservative investors-experiencing previously unthinkable losses of 20% or even 30%.

With diversification no longer the backstop it was once thought to be, institutions have taken steps to protect themselves from future downturns. Remedial steps include bolstering risk management, allocating more money to ‘alternative’ investments such as hedge funds, and adopting or expanding derivatives strategies.

Despite a still-evolving market landscape and myriad challenges, “the traditional investment paradigm hasn’t changed,” Aliaga-Diaz said. “The asset classes that truly create wealth to investors on a long-term basis—assets that yield a stream of future payments (dividend or interest) regardless of the daily swings in their market prices—continue to be the same too. Because of this, a long-term perspective to investing still makes sense.”

EXCHANGES

Exchanges had an eventful half-decade. The incumbent trading venues have had to fight off sustained competition from alternative trading systems while fragmentation in the exchange space itself made for skinnier slices of pie. At the same time, trading volume softened market-wide, and regulators proved unfriendly to exchanges’ plans for big, cross-border mergers.

Rather than be defined by the headwinds beyond their control, exchanges have done their part to take control of their own narrative. NYSE Euronext, Nasdaq OMX and others have diversified their businesses away from just matching domestic stock trades, by crossing borders, adding asset classes, and substantially boosting offerings of technology and market data. They also proved their mettle as market participants’ go-to trading venues in times of trouble, shining through the financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the volatility spike of 2011’s third quarter.

Bill Brodsky, chief executive of Chicago Board Options exchange

“One of the few bright spots during the financial crisis was that regulated exchanges continued to deliver on their mission, with no failures, no closures and no taxpayer rescues,” said Bill Brodsky, chief executive of Chicago Board Options Exchange, the largest U.S. options exchange.

But while traders and investors flock to exchanges in times of stress, the preferred-venue status doesn’t necessarily apply the rest of the time, and alternative venues have largely protected market share captured earlier in the 2000s. About 70% of U.S. stock trading transacted off exchanges in October 2012, little changed from five years earlier, according to industry data.

“What is dramatically different now is that 70% is evenly spread amongst many more stock exchanges, versus just the NYSE and Nasdaq dominating market share five years ago,” said Howard Tai, senior analyst at Aite Group. Indeed, Bats and Direct Edge have ascended to formidable equity-exchange owners, and options exchanges have proliferated as well.

The more competitive climate pushed exchanges to seek merger partners to cut costs and boost scale. A slew of proposed combinations were pending in 2011, including NYSE Euronext and Deutsche Borse, London Stock Exchange and TMX Group, and Singapore Exchange and Australian Securities Exchange. However, the mega-mergers were withdrawn when regulators signaled that the deals wouldn’t fly.

It’s hardly all bad news on the regulatory front for exchanges, who stand to massively benefit from ongoing initiatives in North America and Europe to move over-the-counter derivatives trading on to exchanges. The idea is to leverage the transparency and centralization offered by exchanges to minimize the chance of another great unknown, such as the 2008 credit-default swap market.

“Exchange systems became the prototype for the solutions proposed in the Dodd-Frank Act—OTC derivatives that can be standardized should be traded on exchanges, be subject to central counterparty clearing, or absent central clearing, subject to higher margins,” Brodsky said. “Dodd-Frank will result in more exchange trading, but it’s difficult to know to what degree. Even without Dodd-Frank, the net effect of the global crisis and economic uncertainty may motivate firms to more actively seek the transparency, certainty and guarantees of exchange trading and centralized clearing.”

Exchange leaders don’t always agree—their panels at industry conferences are reliably among the day’s most contentious—but there is broad consensus that the move toward exchange trading is good for the sector, as well as financial markets more broadly.

“The key takeaway from the previous five years is that as investors and market participants, we have a responsibility to learn from past trading and investment practices that have proven ineffective,” said Steve Crutchfield, head of NYSE Euronext’s Amex and Arca options exchanges. “First and foremost, to reduce the likelihood of another 2008 financial crisis or another 2010 ‘flash crash’, transparency in trading and investment needs to improve.”

Exchanges have bolstered risk management at the individual-venue level; in an increasingly connected global market, the next step would be for exchanges to step up their collaboration.

“We believe the trend toward improved risk management will become an even greater focus for the exchange industry and its participants,” said Gary Katz, chief executive of International Securities Exchange. “Up until now, most work in this area has been done at the level of individual exchanges, but as we look ahead toward the next five years, I envision the exchange industry coming together to introduce tools that will allow member firms to manage their risk on a comprehensive basis across the industry.”

Exchanges are poised to benefit by the return of investor confidence and risk appetite, which would channel capital out of fixed income and into equity and equity options, among other comparatively risky securities. Ever-increasing demand for bonds is a trend that “seems close to reaching an inflection point,” according to Tony McCormick, chief executive of Boston Options Exchange.

“My expectation over the next five years is for interest rates to rise, and volatility in the markets to increase which will lift option premiums and restore trading activity,” McCormick said. “Retail portfolios will move out of bonds, and back into equities and equity options. In addition, equity advisors will engage more in the use of listed derivatives both for risk-taking and risk-mitigating strategies.”

The trading-venue landscape, spanning exchanges and alternative systems, increasingly fragmented over the past five years following 2007’s Regulation National Market System, which was designed to encourage competition. The evolution has expanded customer choice and fostered innovation, but the accompanying decline of the New York Stock Exchange as the world’s dominant trading platform is lamentable, in the opinion of James Copell, managing director at Trust & Fiduciary Management Services.

“We have become a system that relies on a computer screen—anywhere in the world,” Copell said. “The Big Board, perhaps as much as any institution in this country, made the U.S. a global financial leader. Remember this when we talk about milliseconds saved and unintended consequences.”

BROKER-DEALERS

There are about 10% fewer broker-dealers now than there were five years ago, and Wall Street mainstays Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns are among those no longer in business. The remaining players are competing for slices from a trading-volume pie that is smaller than it was in 2007.

One trend that has transformed the broker-dealer landscape is the continued expansion of electronic trading.

About 96% of U.S. equity trades executed electronically in 2012, up from 82% in 2007, according to Aite Group. The ascents of other asset classes have been steeper: electronic trading of futures increased from 75% to 94% over the past half-decade, while options rose from 71% to 87%. Electronic trading had accounted for no more than 10% of all futures and options trades as recently as 2001.

The technology and expertise needed to successfully handle trades in a complex, fragmented market structure that works on a rapid-fire basis has underscored broker-dealers’ value proposition.

The sell side has invested significantly in human resources and technology over the past few years and is advertising its liquidity electronically – Serge Marston, global head of E-commerce sales at Deutsche Bank

“Clients now have a clear preference for trading flow products electronically,” said Serge Marston, global head of E-commerce sales at Deutsche Bank. “It facilitates greater price discovery, which in turn enables improved risk management…The sell side has invested significantly in human resources and technology over the past few years and is advertising its liquidity electronically.”

On the regulatory front, one initiative that stands to hold sway over restructurings at both sell-side and buy-side firms is the move to bring derivatives trades from over-the-counter, privately negotiated deals onto public, ‘lit’ exchanges.

“As OTC markets migrate towards an electronic model, the experience gained in the largely electronic equity-trading market will prove a useful template,” Marston said. “To facilitate the change we’re experiencing, there needs to be cross-pollination between the equity and fixed-income desks at the buy side, while the sell side must focus on supplying the tools to support this transition and help mitigate execution risk. These include liquidity aggregation services, DMA access and algorithms.”

Within the broker-dealer space, the battle between traditional, big-bank trading platforms and smaller ‘agency-only’ desks has heated up with order flow scarcer to come by. One one hand, in lean times many traders and investors are more inclined to find a ‘one-stop-shopping’ broker-dealer that offers research and other services beyond just execution, which favors the Bulge Bracket. On the other hand, the regulatory focus on big banks and the associated uncertainty can’t help but be a drag on business development, which favors agency-only shops.

As direct connectors to exchanges and thereby ‘gatekeepers’ of capital markets, all broker-dealers are held to a higher standard than are market participants who have a layer between them and exchanges. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has noted that broker-dealers that provide access to the markets must ensure that they have policies and procedures and systems of controls in place that are reasonably designed to ensure, among other things, compliance with regulatory requirements.

Aside from regulation, the most noteworthy topics from a broker-dealer perspective are the evolution and impact of trading technology and the exponential growth of institutions using both exchange-traded-products and option-centric hedging tools, according to Michael Wallach, chief executive of agency-only broker-dealer WallachBeth Capital.

Even with the proliferation of electronic trading, it has its limitations, and voice and floor will continue to offer liquidity, at least for some trades. “What hasn’t changed is the fact that trading screens remain notoriously one-dimensional despite the three-dimensional nature of financial markets,” Wallach said.

Additionally, market disruptions, geopolitically driven volatility spikes, and diminished investor confidence have sharpened focus on broker-dealers’ fiduciary obligations, Wallach said.

To a certain extent, both bank and agency-only broker-dealers are in wait-and-see mode, not keen on taking risk without more clarity on regulation and the broader economy. For Goldman Sachs, the most important driver of business decisions is what clients do. “As our clients get more active, we will have more opportunities to take risk, and we probably will to some extent,” Goldman Chief Financial Officer David Viniar said on an Oct. 16 conference call to discuss the company’s third-quarter earnings.

“While activity might have picked up a little bit towards the end of the (third) quarter, it was certainly not a very, very large increase at all,” Viniar said. “Traders themselves have to be more comfortable that the market environments are being driven by economics, as opposed to by politics, and I think maybe you’ve had a slight shift to that but not a big shift at all. So I think those are the things to really look for.”

SOFTWARE/TECHNOLOGY PROVIDERS

Tighter regulations and automated trading top the list of trends that have most deeply affected capital markets since 2007, and indications are that both trends have room to run. Software and technology providers developed products and services over the past very difficult half-decade with a clear mandate from budget-constrained customers: give me more for less.

“There are several key themes which we’ve seen appear again and again—regulation, high-frequency trading, the search for alpha and the global shift of economic power,” said Zohar Hod, global head of sales and support at SuperDerivatives.

Events and responses over the last five years point toward a financial-services industry that will be more heavily regulated, but hopefully more stable.

“Technology will continue to enable new financial innovations, trading will be even faster, and settlement cycles will have shortened,” said Jan Ellis Snitzer, chair of International Securities Association for Institutional Trade Communication and vice president at Loomis, Sayles. “Markets will continue to emerge in far-flung areas of the world, prompting new business opportunities…We will see organizations beginning to reap the benefits of having more harmonious global standards, a higher degree of transparency and greater efficiency.”

Over the last five years, there have been substantial advances in automated trading technology, building upon previous developments. “Despite the volatility in markets, the one thing that’s constant is technology and automation,” said Stephen Ehrlich, chief executive of Lightspeed Trading. “Technology improves execution and reduces spreads, enabling institutional traders to fulfill their best-execution obligations.”

Alfred Eskandar, chief executive of Portware

“Advanced front-end solutions have introduced massive efficiencies, reduced operational risk and given traders unprecedented access to global liquidity,” said Alfred Eskandar, chief executive of Portware. “Over the next few years, we’re going to see firms deploying technology that will help traders automatically select and implement the optimal algorithmic strategy, allowing them to increase capacity and improve overall trading performance.”

However, “the current generation of (execution management systems) has taken trade and workflow automation about as far as it can,” Eskandar said. “The responsibility for a trade’s overall lifecycle—analyzing market conditions, selecting the right strategy for a particular order, monitoring execution progress and making any necessary changes—still falls to human traders.”

Regulatory pressures and a heightened emphasis on transparency have increased the need for ‘big data’ management and standardization within financial institutions.

“The global financial and commodity markets have made great strides over the past five years,” said Chip Register, managing director at Sapient Global Markets. “We have seen huge advances across the infrastructure of our industry, driven by the continued evolution of electronic trading and improved centralization and automation of our clearing systems.”

Bringing such functions together “is an industry move to a model where more and more tasks are performed by newly created and shared utilities, as opposed to the old model of every firm having a proprietary infrastructure to manage similar functions between institutions,” Register said. “Such market-led thinking, and the industry working to cure itself of its ills, has led to a much more solid financial infrastructure than five years prior.”

The financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the ensuing regulatory push have sucked up much of the oxygen in the trading-technology space, but there’s a lot going on below the surface as well.

“It’s easy to lose sight of the other significant changes happening that will ultimately impact finance,” said Rohan Douglas, CEO of Quantifi. “A few examples being the changes happening in China, the changing role of social media, and the fact that the world’s internet population has doubled over the last five years.”

Social media could be a medium to boost investor confidence. “There’s a feeling that markets are broken, and to re-establish confidence and trust, some pioneers in electronic trading and market structure are looking at social media to determine whether you can have a stock exchange based on ideas close to Facebook or LinkedIn, so you’ll know your counterparties and you’ll be able to select who you interact with,” said Philippe Carré, global head of connectivity for SunGard’s capital markets business.

Other tech trends will continue making inroads in the financial world, such as outsourcing via the cloud. Also, “a big movement in recent years is operational excellence taking the front seat in the market,” said David Kubersky, managing director of SimCorp North America. “Buy-side firms who figured out that there is a direct correlation between operational efficiency and the growth of alpha, were among the few who grew their assets under management during the financial crisis.”

Cloud is a major IT trend, according to Geoff Hodge, chief executive of Sydney-based technology provider Milestone Group. “The cloud is already winning over financial services firms, particularly in unpredictable markets where flexibility is highly valued,” Hodge said. “We can expect this to continue as senior executives are persuaded that it represents a legitimate alternative to ‘IT mega-department’ models.”

“Devices such as the iPad will also continue to change the way we do business,” Hodge continued. “Executives are directly experiencing how these types of technology with high user engagement change the way people think. With increasing ease of use and accessibility, executives will continue to identify how they can use portable devices to seek game-changing outcomes for their own businesses.”

REGULATION

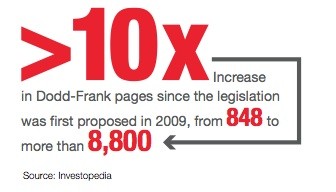

In the area of market regulation, the past five years can be likened to a pendulum that moved essentially the entire arc from less regulated to more regulated.

The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 was caused by a maelstrom of factors, but a lack of sufficient regulation took much of the blame. From a burgeoning but essentially unmonitored credit-default-swap market, to the Bernard Madoff hedge-fund scandal that left market participants questioning the effectiveness of the SEC, to ascendant high-frequency traders that are fingered in most every market disruption, the belief among many legislators, Main-Street constituents, and market participants was that Wall Street needed to be reined in.

So coming off a comparatively laissez-faire period, regulators in North America and Europe mobilized, setting into motion sweeping new sets of rules that will hold implications for most every corner of the market. From Dodd-Frank in the U.S. to MiFID and EMIR in Europe, prop traders, hedge funds, and dark pools stand to be among the most directly affected once the rules are finalized.

Financial-industry veterans say regulatory scrutiny is more intense than it has been in a long time, and the the spotlight will get even brighter before it dims.

“We’re going through a cycle of overregulation,” said Brien O’Brien, chief executive of Chicago-based investment manager Advisory Research. “As an example, the asset-management industry used to be essentially non-regulated, then it went to lightly regulated, and now we’re in the heavily regulated phase.”

The broad intent of Dodd-Frank, which signed into law in the summer of 2010, is to minimize the chance of another financial crisis. The legislation’s main thrusts include moving OTC derivatives trading away from private negotiations and toward exchange trading and central clearing, and severely limiting big banks’ ability to engage in proprietary trading.

Some institutional investors such as California Public Employees Retirement System indicated support for Dodd-Frank on the premise that it would reduce systemic risk, but others have criticized the ongoing regulatory push, especially as one of its already-experienced effects is less liquidity due to market participants pulling back. The swath of new rules embody “overreaction by regulators, and Washington looking for an easy scapegoat,” said Hedger of Fifth Third.

There has been some speculation that Dodd-Frank may be rolled back, but the consensus among market participants is that the pendulum has a bit more to go towards more regulation, at which point it will either hold for a period of time or immediately start the long swing back towards less regulation.

After the experiences of the past five years, it is more difficult to argue that over-regulation is possible, said Hodge of Milestone Group. “This decade will be unprecedented in terms of regulation, and regulators are seeing traditional business boundaries in a different light,” Hodge said. “For service providers, this means being increasingly subjected to operational boundaries that have previously been limited to the regulated entity.”

Possibly the most-decried aspect of regulation is not the rules themselves, but rather their unintended consequences; the Volcker Rule reducing market liquidity is an example of this. But this can also work both ways, as a regulation aimed at one market constituency can help another.

For instance, the imposition of minimum quoting obligations on high-frequency traders will entice more market-making activity.

“We will see more market makers return to the marketplace with quotes staying on the books for longer periods,” said Steven Ehrlich, chief executive of Lightspeed Trading. “We will see more people opt to register as market makers and provide two-sided quotes.”

Market participants generally praise—at least publicly—the intentions of the SEC, CFTC and other regulators, and it has been noted that rulemakers have made significant improvements on multiple fronts, including technology, personnel, and expertise. But even the best-written and best-implemented rule has its limitations. “The problem with regulation is that morality, integrity and good behavior can’t be legislated,” said O’Brien of Advisory Research. “They have to come from good business practices and dealing with ethical people.”

Despite a distinct unease on the part of market participants regarding the ongoing regulatory push, history has shown that Wall Street adjusts to whatever rules it has to work with. Taken one step further, regulation can drive innovation.

“Regulators need to understand that Wall Street is here to make money and allow the flow of funds and credit to keep the economic engine moving,” said Hod of SuperDerivatives. “We have learned that regulations with good intentions that allowed every American to own a home, led to new loan structures and securitization. This may have led to uncontrollable risk taking, but it all started with regulations. Hopefully, we can learn from this history going forward.”

HEDGE FUNDS

Hedge funds were chastened by the financial crisis, but by and large the sector has regrouped with the help of a very large constituency: institutional pension funds.

Large pension funds that allocate at least $1 billion to hedge funds had about 7.5% of their assets invested in hedge funds in 2012, up from 6.5% three years earlier, according to a survey conducted by Infovest21. Los Angeles County Employees’ Retirement Association, Orange County Employees Retirement System, and Louisiana Sheriff’s Pension & Relief Fund are just a few of the public pensions that have reportedly increased hedge-fund allocations of late.

The higher allocations seem a bit paradoxical at first blush, as recent hedge-fund returns have lagged. Hedge funds in aggregate gained about 5% in the first 10 months of 2012, compared with a 14% rise for the S&P 500; funds also underperformed broad market indices in 2011.

“Institutional investors are not looking to time markets,” said Andrew Schneider, chief executive of Global Hedge Fund Advisors. “There are going to be years when the S&P and Dow perform better, but hedge funds are about absolute return—doing well in good, bad, sideways, and upside-down markets.”

As a result of market headwinds and shifting investor needs, the value proposition of hedge funds has shifted from five years ago. Whereas return and alpha capture were once most important, now many investors invest in hedge funds for defensive, safety, and yes, even hedging purposes.

Hedge funds are benefiting from very low interest rates, which reduce the appeal of fixed-income investing. Institutions expect hedge-fund returns to be about 6-8% per year going forward, compared with just 3% for bonds; given the difference, it’s not surprising that Los Angeles County and other pension plans have moved money from fixed income to hedge funds.

But it hasn’t been an easy road back. Similar to the now-debunked belief that diversification is a sufficient protection against big portfolio losses, as recently as the summer of 2008 there was a belief that hedge funds make money in any market, whether rising or falling. But aggregate losses in the order of 20% dispelled that notion.

Aside from the broad devastation caused by the financial crisis, hedge funds were also punished by the nightmarish Bernard Madoff scandal. Since Madoff’s massive Ponzi scheme came to light in late 2008, investor wariness of the safety of hedge funds has ratcheted higher, forcing funds to bolster their own infrastructure and compliance and improve transparency.

It has been business as usual for ‘name-brand’ hedge funds with strong track records, but many smaller, less-established players have had to make concessions to investors on fees and separate accounts.

If properly hedged, hedge funds should return 10-12% per year on average over the long term, according to Schneider. “If that’s the case, institutions would love to have 20% or more of their money there and not have to worry about macro, political or geopolitical issues,” he said.

ALTERNATIVE TRADING SYSTEMS

As their name suggests, alternative trading systems’ mission statement is to provide traders and investors an alternative to incumbent exchanges.

While the first iterations of ATSs offered better pricing and execution on certain types of equity trades, the story since then has also been about branching out into different asset classes and geographies.

“What has struck me over the past five years is the level of innovation that we have seen in the market,” said John Kelly, chief operating officer at Liquidnet. “This has provided the means for investors to seek out growth, yield, diversity, or safety to a degree that was never before achievable.”

Innovation is what propels market structure forward, but it has also at times contributed to market disruptions, a double-edged sword that ATS operators need to take into consideration. “We have a responsibility to continue developing tools that investors need to pursue investment opportunities anywhere in the world, and do so in a way that adds a greater measure of confidence in the systems that have become a critical dependency in facilitating the flow of capital.”

The ascent of high-frequency traders has boosted some alternative trading systems by making exchanges less attractive for institutional investors. O’Brien of Advisory Research noted that his buy-and-hold investment firm has increasingly sought refuge in dark pools so as to avoid interacting with high-frequency traders.

Some of the largest ATSs are run by Wall Street banks, for example Crossfinder, run by Credit Suisse’s Advanced Execution Services, and Goldman Sachs’ Sigma X. In a sign that the lines between alternative trading systems and exchanges have blurred, Credit Suisse reportedly is seeking exchange status for Light Pool, a newer and smaller ATS.

THE NEXT FIVE YEARS

Perspectives vary widely with regard to what can be expected for the next five years in the markets, but there is consensus that the current state hardly qualifies as a true recovery.

“There is a general feeling that we are not completely out of the woods yet,” said Vanguard’s Aliaga-Diaz.

Another notable point of agreement among many market participants is that the extreme capriciousness of recent years makes upcoming years that much more difficult to assess.

“Looking at the most recent past to extrapolate the immediate future can provide some guidance when dealing with a stable and linear process of constant speed,” said Taleb of Robust Methods. “The past decade nevertheless has seen a variety of booms and busts, a substantial acceleration and fragmentation of processes, and a clear rise in complexity. Such characteristics are typicaly those of an organism testing its limits, and usually precede a non-linear shift or a quantum jump.”

Phupinder Gill, chief executive of CME Group

Technology will “not just facilitate ever-faster trading,” said Phupinder Gill, chief executive of CME Group. “Investors will look to technology to promote capital efficiency, the Holy Grail in today’s capital-constrained, lower-return world.”

Despite the intense regulatory scrutiny and state of high alert on the part of market participants, snafus are likely to persist.

“Although technical glitches will hopefully be contained, in the future, they will most likely find their way into the market,” said Hedger of Fifth Third. “I view these interruptions as more of an effect than a cause. The cause is a highly fragmented market which forces greater computing power to be implemented quickly to react to ever-changing market venues and liquidity pools. The effect is market glitches and so-called flash crashes.”

Uncertainty regarding market structure is at a high level given the speed of trading plus recent events, and uncertainty regarding the broader fundamental outlook is also in ample supply. A CNBC survey conducted at the end of 2011 showed that investor uncertainty about the direction of the stock market was at a six-year high, and it’s unlikely that uncertainty diminished in 2012.

One market veteran’s perspective trumped the CNBC survey by a factor of five. “We enter the next five years with a significantly higher degree of uncertainty than any time I can recall in more than 30 years,” said Kelly of Liquidnet.

Kelly noted that a growing pool of liquidity now sidelined will be deployed when investor confidence rebounds, and actively managed equities will be among the asset classes to benefit most. Market structure “will continue to evolve and become stronger from the lessons learned and better positioned to provide the means for renewed growth in global equity markets.”